Editor’s Note: Ruth Ben-Ghiat is a professor of history and Italian studies at New York University and a specialist in 20th century European history. Her latest book is “Italian Fascism’s Empire Cinema.” The opinions expressed in this commentary are hers.

Story highlights

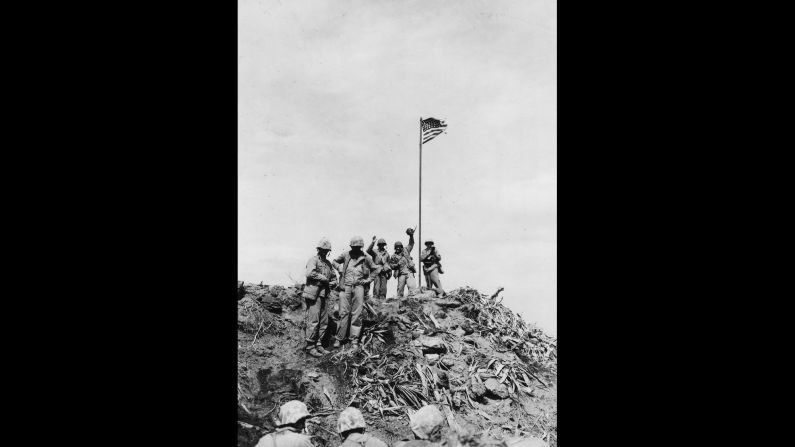

Photos were taken of two flag-raisings on Iwo Jima

Ben-Ghiat: One photo became iconic, representing tragedy and triumph of the war

Seventy years ago, on February 23, two American flags were planted on the peak of Mount Suribachi, located on the Japanese island of Iwo Jima. Coming five days into one of the most ferocious battles of World War II, the first flag-raising, by a group of United States Marines, was emotional, and a Marine photographer captured it.

But a U.S. commander thought the flag was too small to be seen at a distance.

And so, a few hours later, five more Marines and one Navy medical corpsman carried out orders to haul a much larger flag up to the top. Again photos were shot, along with a film. No one thought to record this bit of everyday war business in the daily log.

How did this second flag-raising, and not the other, come to stand not only for the heroism shown during the Battle of Iwo Jima, but the core values of the Marines, and indeed of all American combatants in World War II? The answer is found in the power of certain images, in this case a photograph taken by Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal, to capture a moment but also transcend it.

It might be hard today to comprehend how a single image can become iconic, exposed as we are to streams of photographs and videos every day from our news and social media feeds. But Rosenthal’s image resonated with all who saw it and was swiftly reproduced on U.S. government stamps and posters, in sandstone (on Iwo Jima, by the Seabee Waldron T. Rich) and most famously in bronze, as the Marine Corps War Memorial in Washington. The photograph won a Pulitzer Prize in 1945 and is considered one of the most famous images of all time.

News: The inside story of the famous Iwo Jima photo

Why this photograph, and not the one of the arguably more meaningful first flag placement, which was taken by Staff Sgt. Louis R. Lowery? Its dynamic and masterful composition is part of the secret. The flag structures the picture, its diagonal back-leaning position contrasting with the forward motion of the soldiers. They seem to rise out of the ash and other detritus of the battlefield, and there is already something sculptural in their massed bodies, in their muscular legs and arms that strain to hoist up the heavy pole. The leg of the lead bearer crosses the flagpole, adding a further sense of solidity.

There is something deeply reassuring about this photograph in its display of strength and teamwork – even the last man, who can no longer touch the flagpole, “has the back” of his comrades – and its communication of a push forward to victory.

The fact we cannot see their faces also works to lift the image out of its original context, lending it a universal quality.

In Lowery’s photograph, instead, the eye goes to the face of the wary sentinel, who guards the men who have almost completed their installation. The flag flies free and proud, and all of the soldiers are engaged intently in their task, but they are scattered around the frame. There is no one visual “sweet spot” in this image; it would certainly be harder to reproduce as sculpture.

The gun pointed outward reminds the viewer that this is a very dangerous mission. This photo does not reassure us, but rather makes us watchful. Ironically, this picture of a historic moment of planting an American flag on Japanese soil conveys the everyday jobs of war – guarding, standing around – while Rosenthal’s, of a routine flag substitution, communicates an exceptional and heroic moment.

In truth, both images are necessary to convey the experience of Iwo Jima, which stands today as a notable case of daring strategies of amphibious assault (U.S.) and static defense (Japanese), examples of tenacity and teamwork, as well as failures of intelligence and devastating losses (on both sides).

What made Iwo Jima such a terrible battleground, even within the context of the many tough campaigns of the Pacific Theater? Its primary strategic importance for the United States was as an airbase and staging area for assaults on Tokyo, while the 8.5-square-mile island took on symbolic as well as strategic meaning for the Japanese as the first national soil to face foreign invasion.

The violence of this battle reflected the high motivation of most combatants, but also the particular circumstances of the island. Under the leadership of Lt. Gen. Tadamichi Kuribayashi, the Japanese prepared an extraordinary underground network of tunnels and caves in the semisoft sandstone, from which they would wage their war.

When the Americans landed, Kuribayashi allowed them to advance onto the beach, then opened fire; then, as the Japanese were firebombed out of their hiding places, the beach and environs became a dense killing field,, with hand-to-hand combat not uncommon.

The intensity of battle on Iwo Jima epitomized what author John Dower called “the kill or be killed nature of combat in the Pacific.” For over a month, both sides endured, and saw, terrible things hourly, and yet their resolve only strengthened. The Japanese endured inhuman conditions underground, without food, water, and medical supplies, and their no-surrender policy created more unburied corpses in the tunnels as the war went on.

The Americans endured their own hell above ground, and the chaos of combat in a constrained space made friendly fire casualties higher than usual. Of approximately 20,000 Japanese soldiers, only about 2,000 survived the battle, while the Americans had over 20,000 casualties and 7,000 dead out of a total mobilized force of 70,000. Iwo Jima took an especially large toll on the Marines. One-third of the 19,000 who died during World War II perished on the island.

It is the very brutality of Iwo Jima that made Rosenthal’s polished photograph so necessary and appealing. There is something Olympian about the image on top of the mountain, as opposed to the Japanese in their caves and the Americans their targets on the beach. The subsequent death of three of the flag-raisers in battle only made the photo more compelling as a representation of heroism on the island and as an abstract homage to camaraderie, strength, and determination in battle in general.

It is this perfection that contributed to the unfounded suspicion that Rosenthal’s picture had been staged, and a campaign to restore Lowery’s photo and the first flag-raisers to greater prominence. By then, the picture had been enshrined in the image bank relating to Iwo Jima and had taken on a life of its own, reproduced in sand, ice, and even Legos.

On this anniversary, we might remember both photos, for together they remind us that war is also waged, and won, in the small moments of mundane labor, in obscure airstrips and staging areas as well as major battlegrounds, and in the steady gaze and aim of the single sentinel. The two flags of Iwo Jima offer a lesson for today about the power of the media to shape our notions of what, and who, deserves to be remembered about war.

Read CNNOpinion’s new Flipboard magazine.