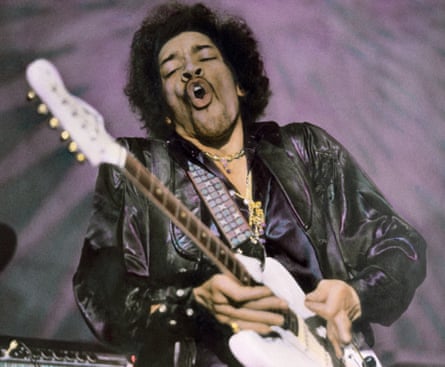

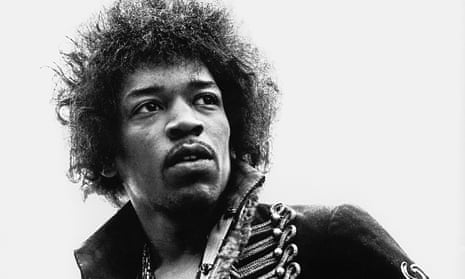

1. 51st Anniversary

Jimi Hendrix introduced himself to the world in December 1966, when he turned Hey Joe, a Los Angeles garage rock standard that had been a hit for the Leaves, into a murder ballad with some wild guitar pyrotechnics. He quickly followed it up with the self-composed Purple Haze, a psychedelic stomper showcasing the devil’s chords (the flatted fifths of the intro were known in medieval times as the diabolus de musica and strictly interdict). As monumental and monolithic as Purple Haze is, 51st Anniversary on the B-side is more nuanced and sassier. . The song continues a theme already explored – albeit somewhat gracelessly – in Stone Free, about Hendrix’s fear of commitment. He did err into misogyny now and again, though 51st Anniversary lays out a balanced case for and against marriage, envisioning the gold, pearl, china and tin anniversaries, and vivid recollections of the cheatin’ third, where nobody gets any presents. While the conjugal subjects can’t wait for the 51st to roll around, earlier marriage milestones are beset with troubles, infidelities and frequent visits to the whiskey house. With the traditional rocky verses juxtaposed against staccato choruses, and the subtle harmonic phrases at the end of each line in the first verse contrasting with the discordant conclusions in the second, Hendrix gives us the good side followed by the bad (and naturally the downside outweighs all the pluses). On tracks such as the gorgeous Drifting, right at the end of his career, Hendrix exhibits a tenderness regarding relationships that was sorely absent early on.

2. Manic Depression

The Guardian’s product and service reviews are independent and are in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. We will earn a commission from the retailer if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.

Animals bassist-cum-impresario Chas Chandler knew he had something special in Hendrix when he saw him playing in a New York basement. He brought Hendrix to London to challenge the established hierarchies of guitar divinity, from Eric Clapton down: “Chas Chandler knew that Hendrix was his secret weapon to demolish the caste structure of London’s hipoisie,” wrote Charles Shaar Murray in his Hendrix biography Crosstown Traffic. Hendrix was quickly teamed up with guitarist-turned-bassist Noel Redding (who’d never picked up the instrument before his audition) and drummer Mitch Mitchell, a jazz prodigy who fused his musical milieu with the outlandish showmanship of Keith Moon; the three-piece would be known as the Jimi Hendrix Experience. The 9/8 jazz shuffle of Manic Depression is a rare time signature for a pop song, but it swings along at a fierce pace, led majestically from the back by Mitchell. If Hendrix was Chandler’s secret weapon, then Mitch Mitchell was Hendrix’s. Hendrix’s lyric is less an exploration of mental illness than a despairing ode to difficult relationships and a desire to form a physical bond with the elusive music itself.

3. The Wind Cries Mary

If The Wind Cries Mary is reminiscent of the interregnum between the end of a party and the laborious clean-up the following day, Hendrix actually wrote it after an argument about mashed potato with his girlfriend Kathy Etchingham, which culminated in plate throwing and flying pots and pans. “After all the jacks are in their boxes / And the clowns have all gone to bed,” he croons over the laziest of accompaniments, “you can hear happiness staggering on down the street.” Hendrix had apparently played it to the band as they were wrapping up a session in the studio, and with 20 minutes left, they laid the track down more or less at the first take. Other versions were recorded, but none had the ambient spirit or spontaneity captured on the original. It was rush-released as a single following the success of Purple Haze, with Melody Maker citing it as Hendrix’s finest moment, displaying “his true flying colours – a lyrical poet combining the deepest feelings with an overpowering, all-enveloping atmosphere and presence”.

4. Bold as Love

Hendrix’s flamboyant style can be traced back to his time playing guitar for Little Richard, from whom he reputedly picked up plenty of performance tricks as well as sartorial advice. Add to that his consumption of LSD during the summer of love, and it seems almost inevitable that all those tie-dyed colours would begin to run into his lyrics. “Fiery green gowns”, “turquoise armies”, “metallic purple armour” and “blue … the life-giving waters taken for granted” all make appearances in the hallucinatory first verse of Bold as Love, while reds, oranges and yellows permeate the second. What Hendrix means by the titular “Axis” in Axis: Bold as Love (the name of the album) we’ll probably never know, but what unspoken beauty is conveyed, even if nobody’s quite sure what that beauty means, exactly. Bold as Love begins with a sharp “anger”, then rides the exquisite, reflective trills of the verses, ending with anthemic guitars carried aloft a mighty musical crescendo, but not before a memorable, phantasmagoric five-second flanged fill from Mitch Mitchell. Bold as Love certainly lives up to its title, and it’s as dynamic and confusing and surprising, too (though unlike love, the song always ends triumphantly, no matter how often you play it).

5. If 6 Was 9

Axis: Bold as Love, recorded in a month during the summer of 1967, is widely regarded as Hendrix’s masterpiece, and at the centre of it all is If 6 Was 9, a hippy anthem a little more caustic than those his contemporaries were recording at the time. The numerological title remains a riddle wrapped up in an enigma, but for all its ambiguity, there seems to be plenty eating Jimi about the burgeoning free love movement, as well as its detractors. “If all the hippies cut off their hair / I don’t care / I don’t care!” he insists, before admonishing white-collar conservatives wagging their “plastic” fingers in disapproval. At five-and-a-half minutes long, it’s an experimental journey of inventive stop/start blues, the acid-fuelled paternal forebear of the more malevolent War Pigs by Black Sabbath. Hendrix uncharacteristically keeps the guitar gymnastics to a minimum, and instead unleashes a psychedelic recorder solo all over the outro as it disappears over the musical horizon.

6. All Along the Watchtower

To take Billy Roberts’ Hey Joe and make it his own was impressive; to do the same with Bob Dylan’s All Along the Watchtower was a coup. Dylan himself was so enamoured with Hendrix’s version that he started to play it closer to the Experience’s arrangement on live outings. Soul and bluesmen from Muddy Waters to Curtis Mayfield can be heard in Hendrix’s playing, but Dylan manifested himself in Hendrix’s lyrics more than any other artist. In that sense All Along the Watchtower sounds like one of Hendrix’s own compositions, aided no doubt by one of his most elegant and soaring solos. There’s no flab, no flubs and no filler – it communicates in a language none of us can speak but we all understand. It’s mesmeric in the way it slips and slides, grunts and grinds, hollers and howls. Hendrix came across an interesting new device deployed by Frank Zappa called a wah-wah pedal, and he soon made that sound all his own, too. It’s still phenomenal when it comes on a stereo somewhere, no matter how many times you’ve heard it.

7. Crosstown Traffic

One of the last songs Chas Chandler had a tight handle on as producer before he and Hendrix parted company over the latter’s working methods (countless overdubs, hangers-on at the studio and so on), Crosstown Traffic is a pulsating groove-based number that’s practically proto-hip-hop, with its skittering drum track and quickfire vocal delivery. Released as a single in late 1968, it is indicative of Hendrix’s shifting focus towards R&B. As Charles Shaar Murray points out, Hendrix never had any trouble as a crossover artist, it was crossing back that was more problematic. In keeping with Hendrix’s spontaneous spirit, the musician grabbed his friend Dave Mason of Traffic – a rock stalwart best known as the guy who wrote Hole In My Shoe – and asked him to contribute backing vocals on the spot; his falsetto can be heard in the chorus.

8. Little Wing (live)

Little Wing is one of Hendrix’s best-loved songs, but this rendering live at the Royal Albert Hall in 1969 trounces the studio version. The vocals are more tender, the improvised outro is exquisite, and even the groaning open note dragged by a whammy bar mid-solo takes your breath away. In the film Wayne’s World, budding axe players are alerted to a sign that says “No Stairway”, but walk into any guitar shop in the western world, and the chances someone will be trying (and failing) to play the opening sequence to Little Wing are reasonably high. The song was inspired by the warm collective buzz Hendrix felt after attending the Monterey Pop festival, where he famously set his Stratocaster alight at the conclusion of Wild Thing. “I got the idea when we were in Monterey and I was just looking at everything,” he said. “So I figured that I take everything I see around and put it in the form of a girl maybe, and call it Little Wing, and then it will just fly away.”

9. Johnny B Goode (live)

If Little Wing is proof of Hendrix’s ability to convey beauty live, then his version of Johnny B Goode perhaps best exemplifies his indomitable power and wild musical aggression in the live arena. Even Marty McFly’s histrionic rendition at the end of Back to the Future is restrained in comparison. Hendrix does things to the guitar that are probably illegal in 37 states. He teases it and makes it scream, he humps the life out of it and strangles it, all the while riding waves of wailing overdrive that in the hands of a mere mortal would be excruciating. When I interviewed Lemmy from Motörhead (a former roadie for Hendrix) in 2010, he said: “I still ain’t seen nobody even now who can master his control of feedback. Because when he played feedback it sounded like an instrument.”

10. Freedom

Freedom, one of Hendrix’s most funky Curtis Mayfield-inspired moments, was released posthumously in 1971 as the lead track from The Cry of Love, a compilation of recordings of songs he’d been working on before his death; the album itself is disappointingly incomplete, with the 1997 compilation First Rays of the Rising Sun perhaps closer to what might have been, although tracks like Hey Baby (New Rising Sun) are still frustratingly not quite polished up enough for the brain to make that extra leap required. Freedom, however, doesn’t suffer from incompleteness – it is a sparkling and fully realised funk odyssey alluding to a familiar need for emancipation, though unusually it doesn’t appear to be about a relationship, with theories including the cloying addictiveness of drugs, and even the demands made on him by the Black Panthers. “Keep on pushing straight ahead,” goes the chanted mantra of the song, and Hendrix seemed to be pushing in a jazz-funk direction, with studio time booked with Gil Evans and the prospect of working with Miles Davis falling through and being revived again on a seemingly monthly basis. Where this might have all led is open to conjecture and has been ruminated upon for nearly half a century, but the mighty back catalogue, recorded over a brief but intense four-year period, is no consolation prize.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion