I walk up and down 57th Street a couple of times before I spot Willie Nelson’s tour bus, Honeysuckle Rose V. Oh, the disappointment! The Honeysuckles of yore – the ones he rode in the 80s and 90s – were gaudy, brown and silver behemoths with western scenes painted on their flanks; this sleek, bullet-grey vehicle has all the character of a special ops van. Inside, there is a vacuum-sealed, aspirin-tasting atmosphere. The air-conditioning is on high, the lighting sepulchrally low. All the surfaces are matt grey or shiny black. When Nelson emerges from his bedroom, with a long braid of yellow-white hair hanging over his shoulder, he looks like Pa Kettle climbing out of a spaceship pod.

Nelson is 82 now, but his face is still magnificent. He’s one of those men who become properly handsome only in late middle age. Although he claims to have been a hit with the ladies from the get-go (“It’s always been a mutual admiration society between me and the girls,” he tells me soon after we sit down in the bus’s grim little kitchen area), one suspects that his early successes had more to do with charm than looks. Photos from the 1950s and 1960s show a decidedly plain, doughy-faced man. It was somewhere in his late 40s, when he started getting leaner and greyer, that his face started to acquire its gaunt, sculptural quality. By the time he hit 60, he was a knockout, a cross between Georgia O’Keeffe and a Cherokee chief.

Nelson is in New York to promote his autobiography, My Life: It’s A Long Story. It’s his fourth book and second full-length memoir. (In addition to Willie: An Autobiography, published in 1988, there has also been The Tao Of Willie, a guide to “happiness in your heart”, and Roll Me Up And Smoke Me When I Die, a scrapbook of personal photos, anecdotes and Willie-style koans.) He was doubtful at first, he says, about the need for, or the seemliness of, yet another book. “I thought there had probably been enough, and I wasn’t sure we needed one more. But then I thought, why not?”

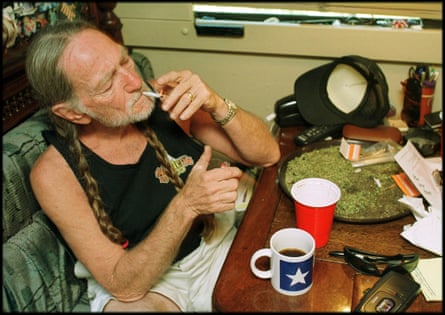

One can think of a lot of reasons a very rich 82-year-old man, who has sold more than 40m albums, written some of the greatest music of the 20th century and been declared an American icon, might decline to spend his dwindling days in a darkened bus, flogging a ghosted book. But Nelson likes to be doing. He likes to keep on keepin’ on. He gets itchy with too much R&R. This year, as well as the book and a new album of duets with Merle Haggard – his 17th in the last decade – he will be launching his own brand of marijuana, Willie’s Reserve. (Nelson has campaigned for decades for the liberalisation of American drug laws, and now that four states have made recreational drug use legal, with more likely to follow, he sees an opportunity to capitalise on his status as America’s favourite stoner. “I’ve bought a lot of pot over the years, and now I’m going to sell some back,” he says.) On top of all this, he will spend 150 nights on the bus, touring. He owns properties in Texas, Maui and Malibu, but his true home, he says, is the Honeysuckle. “If I stay off the road too long, it’s not good for me. I get depressed. The truth is, when I’m not working, I’m not having that great a time.”

He does grow weary of the road, on occasion, but whenever he’s tried to mitigate or avoid the hardships of being on the bus, it hasn’t worked out. He bought a Learjet once, but it was always being grounded due to weather conditions and he found himself missing too many gigs. Another time, he took a six-month residency at a theatre in Branson, Missouri. It was a disaster. He hated staying in the same hotel suite night after night, hated feeling “like a factory worker”. He pitched a tent in his suite and pretended he was camping in the woods, but even that didn’t take away the ennui. As soon as he was able, he went back to the bus. “Oh, there are nights when you think, ‘I wish I could stay home tonight,’” he says, “but it’s never serious. And when I get out there, I’m always glad. First of all, it’s a great workout for me and my lungs to sing for an hour and a half. It’s some of the best physical exercise a person can do. The more I work, the more I feel I’m capable of working and the more I like it.”

Nelson’s hearing is beginning to go, and when I saw him at Radio City Music Hall last year, his gorgeous whine of a voice sounded a little weak. But when I ask about the state of his vocal cords, he is adamant his voice is as strong as ever. “There are songs I sing better now,” he says.

Which ones?

“All of them.”

You mean, you’re interpreting them better?

“No, I think I’m singing better than I did 40 years ago.”

I should acknowledge at this point that I regard Nelson as one of the great geniuses of popular music, a man whose contributions to the American songbook rank up there with those of Ray Charles or Nina Simone. I named my daughter, Louella Nelson, after him. So whether his voice is a tiny bit weaker, or not, I still think it’s worth going to see him in concert. If nothing else, you are witnessing the twilight of a god.

Nelson grew up during the Depression, in the tiny town of Abbott, Texas. His mother, Myrle, left home six months after he was born and went off west to work as a dancer, waitress and card-dealer. (His older sister, 84-year-old Bobbie, the pianist in his band for the last 50 years, says Myrle is the person from whom Nelson inherited his restless gene.) Willie and Bobbie were raised by their saintly-seeming paternal grandparents, Alfred and Nancy. “Might sound corny,” Nelson writes in his memoir, “but the truth is we were dirt poor in material possessions, but we were rich in love.” Alfred was a blacksmith; Nancy picked cotton and gave piano lessons. Both were musical and encouraged the children’s musical talents. “They would take correspondence courses from the Chicago Music Institute,” Nelson says. “I can remember them sitting round the table at night beneath a kerosene lamp, studying their music, so I grew up with that, with people who took music seriously. I learned a lot before I ever left the house. I learned about what I wanted to do.”

Nelson wrote his first song when he was seven, and at 10 began playing guitar in a polka band. His grandmother was troubled by his playing in night clubs. “She had warned me about all the sinful things that go on in beer joints,” he recalls, “and when she heard I was going to play in a place six miles away, she said, ‘You promised me you would never go on the road.’ Six miles down the highway was on the road to her.” Nancy, a “very, very hardcore, church-going Christian”, inculcated Nelson with a strong faith that has stayed with him. But from an early stage, it seems, he respectfully dissented from some of the church’s more trying prohibitions – particularly the ones having to do with wine, women and song. “A hard dick has no conscience,” he likes to say.

The values of the community in which he grew up were both conservative and surprisingly liberal, he says. “I mean, everybody sort of minded their own business and nobody cared what you did or didn’t do, as long as you didn’t bother them.” This interesting definition of liberalism is a clue to the essentially libertarian nature of Nelson’s politics. People sometimes express wonder at the fact that a man with such progressive views on LGBT rights, drug laws and so on should be considered a national treasure, but the truth is, most of his positions speak to a fundamental American principle about personal freedom and the right to be left alone. Another reason his politics have not got in the way of his popularity is that he rarely proselytises. “I entertain people,” he says. “That’s my job, and I do it with my music. I think that’s what people want to hear when they come to a show. I never talk about politics on stage.” In fact, he is reluctant to debate politics, even with friends. When I ask if he ever argued with Merle Haggard or Johnny Cash about their conservative views, he shakes his head impatiently. “I could care less what people think or want to do politically. Everybody has a right to be what they want to be and say what they want to say.”

Nelson married for the first time – there have been four wives – at 19. He and 16-year-old Martha had three children – he has seven in total – and they spent most of the 1950s moving from state to state, trying to find day jobs to support the family while Nelson pursued his music career in honkytonks at night. He found various employment – as a door-to-door salesman of vacuum cleaners and encyclopedias, as a plumbing assistant, as a gas pump attendant and as a DJ – before finally, in 1960, emboldened by selling his first song, Family Bible, for $100, he moved to Nashville. Within a year, he had made a name for himself as a songwriter. In 1961, Faron Young recorded Hello Walls, Patsy Cline recorded Crazy, Billy Walker recorded Funny How Time Slips Away and Ray Price recorded Nightlife – and all four were top 20 hits in the country charts. Nelson got a recording contract with Liberty Records and then RCA, and over the next decade made 14 albums; but none of them took off, and his singing career remained stalled.

One of the most distinctive features of Nelson’s singing is the loose, casual-sounding way he varies the phrasing of a lyric, laying back on the beat or jumping ahead of it, but always staying within the meter. In the early days, the unorthodox “rubato” style of his delivery wasn’t always appreciated by record executives, some of whom accused him of “speaking his songs”. In An Epic Life, Joe Nick Patoski’s biography of Nelson, Tommy Allsup, who produced some of Nelson’s records in the early 1960s, describes the difficulties session players had in adapting to his style: “He sang behind the beat. That’s the way jazz singers sing. If you recorded with Willie, I don’t care if you knew the song backwards, you better write out a chord chart and read that sumbitch. He’s going to be away from the lead line. That’s what we’d do. If you start listening to him while he’s playing, you’re going to break time.”

Nelson claims he never doubted his own abilities as a singer. “Growing up in Texas and working the clubs there, all the folks would come out and see me, and they seemed to like my singing well enough. Whether my singing could sell records or not, that was another story. Record companies weren’t that turned on by my phrasing, and it wasn’t exactly what was going on in Nashville at the time.”

Part of the problem was that, in the studio, producers tended to augment his spare style with the lush strings and celestial choirs that were standard to country music at the time. “They kept fooling with the music when I knew it needed to be simpler. I felt I knew more than they did, because I saw it every day and they were only looking at numbers. I knew I had an audience. I just had to make a decision and say, this is the way I’m going.”

In 1971, Nelson moved to Austin. The decision to leave Nashville was considered by some to be career suicide, but in Austin he found a hippie scene that suited him and was receptive to the elements in his music that Nashville found “weird”. He abandoned the suits and ties he’d been wearing on stage for a more laidback, longhaired look and ordered his band to do so, too. “I noticed that everyone [in Austin] dressed very comfortably, wearing jeans and tennis shoes and T-shirts, and every time I showed up in a suit and tie, I felt a bit out of place. I felt like I was outdressing my audience, so I decided to make it easier on me and dress the way they dressed. It was the way I had dressed all my life, anyway – T-shirts and blue jeans – so it was an easy change to make.” It was the beginning of the bandana, beard and braids look that would be his signature sartorial style ever after.

When Jerry Wexler signed Nelson to Atlantic Records soon after, he gave him creative licence in the studio, and for the first time Nelson found himself able to record his songs the way he wanted, using his own band rather than session musicians and leaving out the piped-in choirs. By 1975, he was being described by the New York Times’ music critics as “the acknowledged leader of country music’s left wing, working to cleanse Nashville of its stale excesses by bringing it up to the present and its own folkish roots”.

That description was true enough in its way, but slightly misleading in that it attributed to Nelson’s music a missionary purpose and a purist ethos it never really had. If Nelson has anything that might be described as a musical philosophy, it is that genre boundaries exist to be crossed. His favourite guitarist is Django Reinhardt, his favourite singer Frank Sinatra. “There’s always been people who say, ‘That’s not country, why’re you doing that?’ Or, ‘This would be a better song for you.’ Record company executives are the worst at it. They think they know everything. And, you know, sometimes they know a lot and sometimes they don’t know anything.” He cites Columbia’s reaction to his 1977 announcement that he wanted to record an album of American standards. “They didn’t see it, they didn’t understand it, and automatically they said it wasn’t a good idea. I went ahead and did it anyway, because I had it in my contract that I had creative control – I could record anything I wanted to. They had to back off and take it, and when it wound up a number one record, they all said, ‘Well, look what we did!’”

You can see why the people at Columbia might have had misgivings about their newly minted country outlaw star singing covers of songs made famous by Lotte Lenya and Louis Armstrong: other artists with fantastic voices, such as Rod Stewart, have attempted similar things with gruesome results. But the album, Stardust, is one of the most sublime things Nelson ever recorded (as well as one of the most commercially successful). You could not have predicted it, but his interpretation of September Song is every bit as beautiful, perhaps more so, than the original.

Not all Nelson’s forays into non-country territory have had such satisfactory results, however. His cover of Nirvana’s Smells Like Teen Spirit, for example, or his reggae album, Countryman, or his duet with Julio Iglesias, To All The Girls I’ve Loved Before – a recording characterised by “stale excesses” if ever there was one – are all pretty grim. He has released well over 350 albums in the course of his career, and the “why not?” spirit in which he is now publishing a second memoir seems to sum up his approach to recording, also. Nelson is not an artist who approaches each new album as a crucial summation of his artistry. He takes a much more relaxed, hit-and-miss approach. “The whole music business is built around the idea of releasing one gigantic album every couple of years,” he writes in The Tao Of Willie, “while my idea is to play as much music with as many great musicians while I can.” With music, as with golf, he says, “If you care too much, you’ll screw it up”. “I don’t think it’s possible to be perfect all the time. My playing, my singing, my writing, it all has flaws. If I like a song, I’ll record it and that’s pretty much it. If I’m happy with it after a couple of takes, I leave the studio. It’s a little late to worry about it afterwards.”

There’s something wonderfully unvain about this approach, but there’s something odd, too, about the lack of discrimination – Nelson’s apparent indifference, or obliviousness, to the mediocrity of some of what he has released. When I ask which of his recordings are personal favourites, he seems to make no distinction between what’s good and what’s popular.

“It’d be a hard choice,” he says. “The people have said that they like Crazy – that’s the people’s choice. Patsy’s version of it has sold millions of records. A lot of people got to hear that song and my music generally because of her.” This is rather like asking Beethoven which of his compositions he values most highly and having him refer you to the opening bars of the Fifth Symphony.

Right, but what’s your favourite? “For myself, it’d be hard to say. I do a lot of songs. Every night I do Crazy, Funny How and Night Life in a medley, so, naturally, those three songs are important to me. Then there’s On The Road Again and Angel Flying Too Close To The Ground.”

It seems impossible that Nelson could regard Funny How Time Slips Away, a sly, exquisitely melancholy song about meeting an old lover, as melodically or lyrically in the same league as the banal anthem that is On The Road Again. Does he really mean it? It’s impossible to know. He is not a man who enjoys prolonged analysis. His preferred conversational mode is breezy, jokey, aphoristic. It is, perhaps, one of the reasons he has been happy to cultivate his essentially comic public persona as genial stoner and Zen Bubba: it deflects tiresome scrutiny.

“I’m a very private type of guy, overall, I think,” he says. “I’ve never minded fame. I’m very lucky to have fame and fortune and all that good stuff. But I think it’s interesting that, after all the songs that I’ve written – and I felt like I expressed myself the best I could in those songs – and after all the books that have come out, it’s interesting that people still have questions.” He smiles. “I can’t imagine anybody could have anything more to ask.”

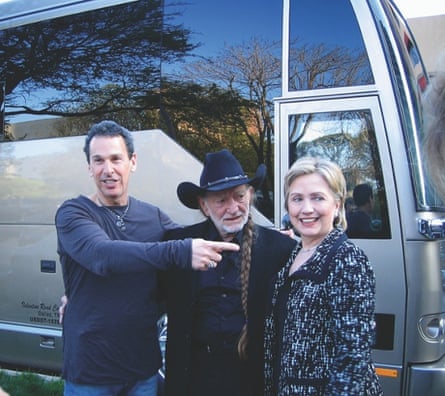

At the end of the interview, I give Nelson a copy of my first novel, which has the lyrics from his 1959 song Man With The Blues as its epigraph, and ask him to sign it for my daughter. Then Nelson’s assistant offers to take a couple of photos of us on my phone. When I get home and show my daughter these prizes, she is largely unimpressed. (She is 11, and not yet sold on the idea of being named after a wizened country singer.) Nelson’s inscription – “To Louella Nelson, love Willie Nelson” – is barely legible, she points out, and the photos horrible, with Nelson looking haggard and a bit desperate, and me sweaty and on the verge of tears. But do I care? I do not. I print them out and stick them on my fridge, where they have remained ever since – an ill-lit and slightly fuzzy record of my encounter with greatness.

- My Life: It’s A Long Story, by Willie Nelson, is published by Sphere on 21 May, priced at £20. To order a copy for £16, call 0330 333 6846 or go to bookshop.theguardian.com.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion