- Researchers have spotted water in the rocky-planet-forming region of a star.

- The James Webb Space Telescope has spotted significant amounts of water vapor around a young star 400 light years away.

- Scientists hope that this will provide new insight into how exactly Earth-like planets get their water.

We have several theories about where all of the water on Earth may have come from. Some say it may have hitched a ride on a meteor, while others say it could have come from white-hot magma interacting with hydrogen in the atmosphere.

Most likely, it’ll be quite a while before we figure out how our own oceans came to be. But in the meantime, we can investigate where water comes from on other worlds. And beyond the options our own world has, there’s another alternative water source for rocky planets: they could form with the water baked right in.

According to a new study, scientists have now seen—for the first time ever—water in the rocky-planet-forming region of a star’s protoplanetary disks. These disks orbit around stars and are full of the gas and debris that can eventually coalesce into brand-new planets. And right where the rocky planets would be forming around one particular star, we found water.

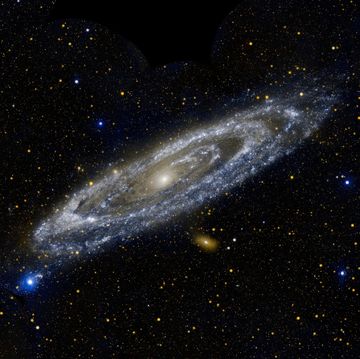

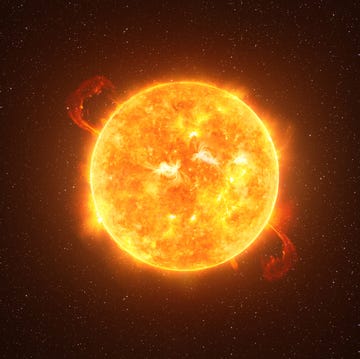

The star in question is called PDS 70. It’s just a baby at only 5.4 million years old (our Sun is a cool 4.6 billion), it’s about three-quarters the mass of our Sun, and it’s cooler. It’s already got two planets in its orbit, and it may someday have more.

All things considered, it’s pretty similar to a young version of our Sun, which is why we turned the observation powers of the James Webb Space Telescope its way. “By observing it,” Giulia Perotti, lead author on the study, told Space.com, “we can trace back how the planets in our solar system formed and what their chemical composition was before they fully formed.”

Now, the water they found wasn’t just big blobs of liquid floating around. It’s in the form of water, hovering around 625°F. But if any planets do form in that region, they’ll be able to scoop up that water, raising their chances for habitability later on in their lives.

For a long time, researchers thought it might be impossible to have water in the terrestrial-planet-forming regions of protoplanetary disks like this none. We had never seen it before, and researchers theorized that the stars may burn it all off before planets would have the opportunity to collect it for their own during the formation process.

But these observations say otherwise. The research team believes that this may be due to other particles in the area effectively shielding the water vapor particles from the full force of the nearby star. While 625°F is an incredibly high temperature, it would apparently take more than that to burn all the water away.

Now, the researchers are looking forward. They hope to be able to not only make more observations of this system and even more thoroughly catalogue what this excitingly watery disk is composed of, but expand those observations to other, similar systems in order to see just how common this water is. Maybe someday, we’ll even see some baby planets forming in a region like this—and learn something about our own Solar System in the process.

Jackie is a writer and editor from Pennsylvania. She's especially fond of writing about space and physics, and loves sharing the weird wonders of the universe with anyone who wants to listen. She is supervised in her home office by her two cats.