The California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) is seeking comments on the appropriate pest rating for Leptosillia pistaciae, a recently discovered fungus that causes pistachio canker.

The Department’s draft pest ranking assigns the highest Economic Impact score – three. It assigns a medium Environmental Impact – two. This is because the pathogen can kill an important native shrub, with possible follow-on consequences of reduced biodiversity, disrupted natural communities, or changed ecosystem processes.

CDFA states that there is no uncertainty in its evaluation, but I see, and describe here, numerous questions about the possible true extent of the invasion and possible host range.

Comments are due on April 4, 2020.

The pathogen was detected in June 2019, when a habitat manager from an ecological reserve in San Diego County noticed multiple dead lemonade berry shrubs (Rhus integrifolia) in one of the parks. This is the first known detection of Leptosillia pistaciae in the United States and on this host. USDA APHIS has classified Leptosillia pistaciae as a federal quarantine pest. Rhus and Pistacia are in the same family, Anacardiaceae (cashews and sumacs).

According to the CDFA, Leptosillia pistaciae is the only member of this fungal genus known to be associated with disease symptoms on plants. Other species are endophytes or found in dead plant tissues. [It is not at all unusual for fungal species to be endophytes on some plant hosts but pathogenic on others. A California example is Gibberella circinata (anamorph Fusarium circinatum), which causes pitch canker on Monterey pine (Pinus radiata) but is an endophyte on various grass species (Holcus lanatus and Festuca arundinacea).]

(Reminder: this is the second new pest of native species detected in California state in 2019; I blogged about an ambrosia beetle in Napa County here. )

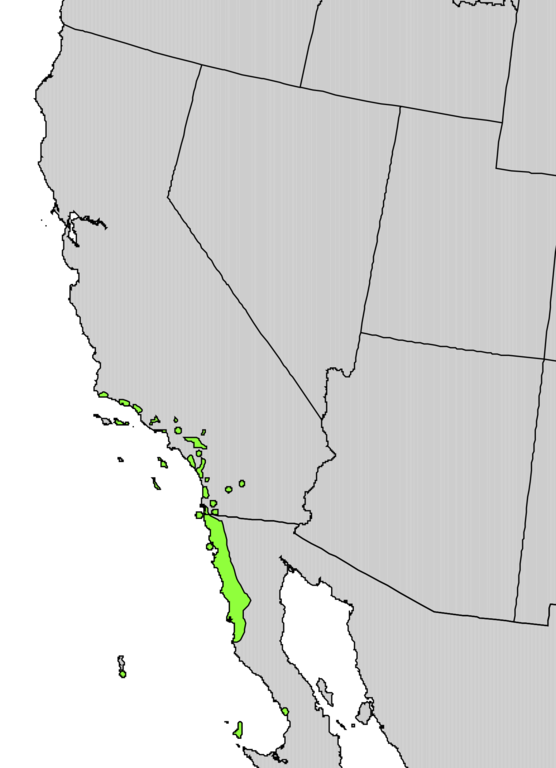

Rhus integrifolia (lemonade berry or lemonade sumac) is native to California. It grows primarily in the south, along the coast – from San Diego to San Luis Obispo. However, some populations are also found in the San Francisco Bay area. This and other sumacs are also sold in the nursery trade.

On pistachio trees in Italy, symptoms are observed in the winter and late spring. During the winter dormant season, trees had gum exudation and cracking and peeling of bark on trunks and branches. On trunks and large branches, cankers appeared first as light, dead circular areas in the bark; subsequently they became darker and sunken. Under the bark, cankers were discolored with necrotic tissues; in some cases, these extended to the vascular tissues and pith. During the active growing season, the symptomatic plants also showed canopy decline. Inflorescences and shoots, originating from infected branches or twigs, wilted and died. When the trunk was girdled by a canker, a collapse of the entire tree occurred.

On lemonade berry, large clumps of dead adult shrubs were observed on the edge of hiking trails. Some shrubs that had completely dead foliage were re-sprouting from their bases. Trunks of shrubs that were not completely dead were copiously weeping sap and fluids and showed foliage browning and die back with symptoms of stress.

It is thought that spores could be spread by wind, rain splashing, and the movement of dead or dying trees, greenwaste, and infected nursery stock. Contaminated pruning tools might also transport the spores. The possibility of a latent phase – or perhaps asymptomatic hosts – adds to the probability of anthropomorphically assisted spread.

I question how much effort has been put into detection surveys, especially in natural systems with native Rhus species. California has three other native sumacs: R. ovata, R. aromatica, and Malosma laurina (CNPS; full citation at the end of the blog). In addition, there are numerous other species in the family, including poison oaks (Toxicodendron spp.) and the widespread invasive plant genus Schinus.

Furthermore, some plants in the family (other than pistachios) are grown for fruit or in ornamental horticulture, including two of the native sumacs and two non-native species, Rhus glabra and R. lanceolata, cashew, mango, and smoke trees (Cotinus spp.).

Yet CDFA confidently states that there are only two hosts and that it has been detected in only one population – that in San Diego. This is because CDFA considers only official records identified by a taxonomic expert and supported by voucher specimens.

CDFA states that the pathogen is likely to survive in all parts of the state where pistachios are grown – primarily in the Central Valley. California supplies 98% of the pistachios grown in the United States; the remainder is raised in Arizona and New Mexico. California production occurred on 178,000 acres in 2012. A map is included in a flyer on production available at the url listed at the end of this blog.

In discussing spread potential, no mention is made of possible human-assisted spread.

The CDFA document includes instructions for submitting comments; the deadline is April 4.

Sources:

Rhus and related species native to California: California Native Plant Society

https://calscape.org/loc-california/Rhus(all)/vw-list/np-1?

Rhus species used in horticultural plantings in California: CalFlora https://www.calflora.org//cgi-bin/specieslist.cgi?where-genus=Rhus

Pistachio production information: https://apps1.cdfa.ca.gov/FertilizerResearch/docs/Pistachio_Production_CA.pdf

Posted by Faith Campbell.

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

My lemonade Berry bushes are getting wiped out. The condition I see looks like rats or squirrels have been eating the bark around the base of a limb, however, no obvious tooth marks. The plant is oozing sap trying to heal. We have had rats and squirts for a million years but this problem has only occurred in the last two years. Could it possibly be a fungus?

I regret that I cannot diagnose the problem with your plant. I urge you to contact your county Agriculture Commissioner and / or Dave Pegos at the California Department of Food and Agriculture to ask them to diagnose the plant. I hope you will inform me of the results!

Are you in the coastal southern California region where the pathogen appeared? Or elsewhere in the state?

My 30-foot tall lemonade berry is leaking dark sap. I live near Trabuco Canyon in Orange County. I will contact my county agriculture commissioner to ask for a diagnosis. Thank you for sharing this information!

Please tell me whether the Ag Commissioner’s staff thinks your lemonade berry is infected by Leptosillia pistaciae,