There’s a feeling — not quite nostalgia, and not wistfulness, but something more poignant and urgent — that overwhelmed me entering Sonja Ahlers’s Classification Crisis. The sight of Sonja’s familiar materials: the ballet shoes, the bunnies, and that perfect handwriting — both the bubble letters of my deepest elementary school desire, and yet, somehow punk — created a portal that, rather than transport me into the past, brought the past to me in the present.

I first met Sonja in mid-90s Victoria when, as early twenty-somethings, we all rode bikes around the city in our West Coast riot grrrl outfits sourced from Victoria’s Value Village (IYKYK). I will admit I thought I was pretty cool, but I also knew that Sonja was cooler. With found images (sourced from the very same Value Village), some simple office supplies (8 ½ x 11 paper, staplers, black felt-tip pens), and a Kinko’s copier, her zines and collages reflected our lives. Early adult anxieties about love, financial precarity, mental illness, and the suffocating pervasiveness of the patriarchy were articulated through flowers, bunnies, and pop-culture references equal parts Holly Hobby and VC Andrews.

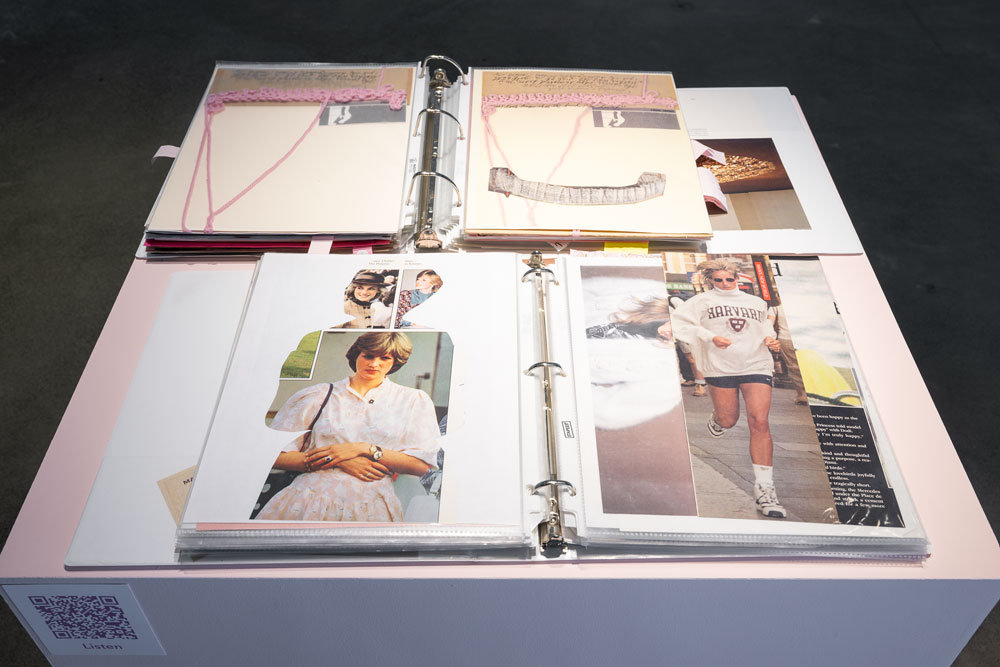

Throughout the exhibition, sculptures comprised of boxes and binders containing Ahlers’s years of accumulated material stand as evidence of the artist’s constant recombinations: the past continually reconstituted into the present. The Archive (2014–2023) is a recreation of the storage system she has established in her Victoria home to create a sense of order over her materials. Sticky notes adhered to a seven-by-seven stack of cardboard banker boxes show a deeply personal classification system that includes categories “Temper, Temper,” “Rookie,” and “Swan Song,”delineating past book projects and their source materials. Less defined but no less meaningful are the categories “to sort” and “mail from boys.” Other, what we might call “binder-based,” works such as Swan Song (2021) and unshown binders (2008–present) are neatly arranged on plinths, allowing visitors to browse through the source materials that she continues to reconfigure, reformat, and reclassify. In the case of Swan Song, the materials she has discarded — a pile of crumpled 8 ½ x 11 paper lying directly adjacent to the plinth of binders — also attests to the sense of letting go of the pieces that no longer work.

Rabbit Hole (2022–23), one of the newest works in the exhibition, is similar to other works in the show in its use of images, themselves framed and unframed, mined from her active archive. Through her use of colour (something normally lacking in Alhers’s work, aside from her enduring love of all shades of pink), she goes deeper into the complex relations between beauty ideals and feminism, while also communicating a sense of exhaustion with it all. This exhaustion is made plain by the large cut-out image of a sleeping (but still luminous) Princess Di and a Beatrix Potter bunny with her head in her hands situated directly below the handwritten text “It’s All Work.” But to what is she referring? The negotiation of her own place in the artworld? Her own unwieldy archive to which the show’s title refers? Perhaps all, and perhaps none. In a video interview on display in a side gallery, Ahlers articulates how her gloriously fluffy and iconic Fierce Bunnies (a selection of which are contained in an adjacent vitrine) have “become more peaceful over time.” Maybe Rabbit Hole references less exhaustion and frustration, and more peace with her own process and practice.

Ahlers and curator Godfre Leung use investigatory language such as “evidence,” “crime scene,” and “murder wall” throughout the exhibition materials to describe the cool arrangement and display of Sonja’s work. But to me, Classification Crisis is far less violently forensic. It is evidence, for sure — but not of a crime. It’s evidence, rather, of a life and process that marks the passage of time, even if it continues to feel like no time has passed at all.

A hybrid exhibition catalogue and new book project, also titled Classification Crisis, was co-published by Conundrum Press and the Richmond Art Gallery in 2023 and can be found here.