Editors assigned to write their newspaper’s next editorial should first think about the last argument they actually won.

Maybe, young scribe, it was the time you convinced your dad that you really did need the new iPhone. Or the time you persuaded your mom to extend curfew so you could attend a concert. I imagine you were at your best during those times, mixing passion with a some cold, hard facts. If you made your point quickly and stayed focused, chances are you won your argument, or at least a measure of respect.

Now you are ready to write that editorial.

Being a father of two sons AND a journalism teacher, it surprises me that writers at school seem to forget the persuasive techniques that often work at home. Begin with the problem. And it doesn’t matter if the problem is the cost of the Homecoming dance or whether you’re responsible enough to drive to school. You have your point of view. You’ve done your research. Now, you must convince someone else — a parent, teacher, sibling or reader — that your argument deserves consideration.

Yet too many editorial writers seem convinced that the best way to win a argument in print is to “filibuster” the subject; that is, discuss it to death without regard to form or function. Returning to my opening premise: How many arguments have you won lately by ranting about it day after day? Emotional appeals may win sympathy, but it takes a rational approach to win converts.

The tendency toward long editorials — even when topics are timely and relevant — reminded me of the toughest class I ever took as a journalism undergraduate. Okay, that was a long time ago but I still think the story is relevant.

My professor was notorious for an “Opinion Writing” course he taught because he would not accept any editorial longer than 300 words. That’s only about eight tightly-written paragraphs. To succeed in this class, I would need to check my ego at the door and realize that nobody really cared about my magic prose or convoluted opinions. If I could learn to state my case succinctly and powerfully, I would pass the course. If not, well, there were other majors.

Fortunately, this class taught me a valuable lesson about all good writing. The best writers have a clear sense of what they want to say and they communicate their ideas in a compelling, non-threatening way. There’s beauty (and power) in simplicity. Clean, persuasive writing can move readers toward some form of action or behavior if certain key elements are present.

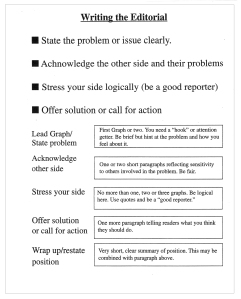

Which brings us back to the editorial as a reasoned argument designed to convince the reader to act or think in a certain way. There are four elements I would like to explore (See graphic left).

Which brings us back to the editorial as a reasoned argument designed to convince the reader to act or think in a certain way. There are four elements I would like to explore (See graphic left).

To see these four elements at work, let’s look at a recent editorial piece from the Crown Point Inklings staff who decided to take a stand with regard to a change in the traditional Homecoming dance.

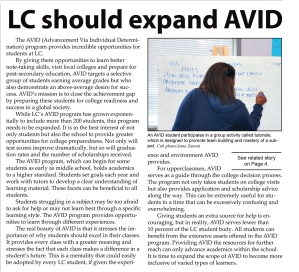

The first requirement of strong, persuasive writing is to clearly state the problem at hand: A new Homecoming dance format adopted by the Crown Point administration attempted to be more inclusive by creating a more informal, less expensive event. However, the post-Homecoming dance still cost student $40 and conflicted with the timing of the game. Students also had to take the SAT the next morning (See first graph of editorial below left). It didn’t help that administrators did not include students in their decision-making process.

Fair-minded staffs understand that the best way to disarm opponents is to acknowledge the other side. I would add that if the editorial is taking a stand against an administrative policy or idea, it’s critical that the editorial writer be a good reporter first and fully report the administration’s position. In this second requirement of successful editorial writing, The Inkling staff tries hard to understand the reasoning behind the change in the Homecoming dance. (See second paragraph).

Fair-minded staffs understand that the best way to disarm opponents is to acknowledge the other side. I would add that if the editorial is taking a stand against an administrative policy or idea, it’s critical that the editorial writer be a good reporter first and fully report the administration’s position. In this second requirement of successful editorial writing, The Inkling staff tries hard to understand the reasoning behind the change in the Homecoming dance. (See second paragraph).

The third requirement of the successful editorial is critical because it should reflect logical arguments for a better solution. Good reporting is the key here. The Inkling staff does this with a third paragraph that points out the pros and cons of the informal dance approach. Clearly, the staff has done its homework and persuades on the basis of facts.

The fourth requirement may take one or more paragraphs to issue a call to action. That means the staff (or editorial board) has thought about the problem and found a solution that should satisfy the student body (and administration, hopefully). Again, the Inkling staff writes another long final paragraph to clarify the situation and offer a call to action.

The final sentence of the fourth paragraph should be a separate paragraph simply to distinguish it. Good editorial often use a final sentence or two to wrap up the argument and restate its position.

Okay, let’s review. For editorials to be effective, they must be tightly written — 300 to 350 words usually.

• The first graph or two of the editorial should “hook” the reader by stating the problem but also hinting at how the staff feels about the issue at hand.

• The next graph or two should reflect sensitivity to others involved in the problem. Be fair. Acknowledge alternative points of view.

• Use one, two or three graphs to stress the staff’s side of the argument. Here’s where good reporting comes in. Use direct quotes from key sources to strengthen your argument. Be logical. Fight for what you think is right. And back it up with facts.

• Write one more paragraph telling readers what you think they should do (or maybe how they should view a situation). This is your “marching orders.” Editorials without a call to action tend to lack authority and fail to persuade.

• It’s okay to end the editorial with the call to action; however, the editorial writer might want to add one more sentence or two to wrap up and clarify the staff’s position. Sometimes, this final sentence can be combined with the above graph or isolated into a separate graph for emphasis.

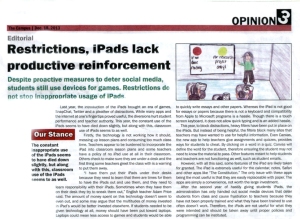

I’ve included a few additional examples of editorials that satisfy the four basic elements of strong editorial writing. See if you can identify each of the four elements in the samples below. Also ask these “test” questions about these sample editorials:

• Is the problem stated clearly and do these editorials show how readers are affected?

• Do these editorials take a clearcut stand and include “marching orders”?

• Is the reasoning sound? Is there evidence of good reporting?

• Do these editorial also acknowledge the other side?

• Do these editorial open with power and close with purpose?

♦Providing expanded AVID Program For LC Students

♦New Blocking Software Does More Harm

Than Good At Munster

♦Restrictions, iPads Lack Productive Reinforcement At Huntington North

And one last point. Good editorial writing is also good leadership. It’s not about always being “right.” Instead, it’s about starting a meaningful conversation about issue in the school community that matter. When newspapers staffs lead editorially, students have a voice. And when those voices are passionate and fair minded, the school is a better place.

Leave a comment